Felice Beato

Felice Beato (1832 – 29 January 1909), also known as Felix Beato, was an Italian–British photographer. He was one of the first photographers to take pictures in East Asia and one of the first war photographers. He is noted for his genre works, portraits, and views and panoramas of the architecture and landscapes of Asia and the Mediterranean region. Beato's travels to many lands gave him the opportunity to create powerful and lasting images of countries, people and events that were unfamiliar and remote to most people in Europe and North America. To this day his work provides the key images of such events as the Indian Rebellion of 1857 and the Second Opium War. His photographs represent the first substantial oeuvre of what came to be called photojournalism. He had a significant impact on other photographers, and Beato's influence in Japan, where he taught and worked with numerous other photographers and artists, was particularly deep and lasting.

Contents |

Origins and identity

The origins and identity of Felice Beato have been problematic issues, but the confusion over the dates and places of his birth and death seems now to have been substantially cleared up. Based on a death certificate discovered in 2009, Beato is known to have been born in Venice in 1832 and to have died on 29 January 1909 in Florence. The death certificate further indicates that he was a British subject and a bachelor.[1] It is likely that early in his life Beato and his family moved to Corfu, at the time part of the British protectorate of the Ionian Islands, and so Beato would have qualified as a British subject.[2].

Because of the existence of a number of photographs signed "Felice Antonio Beato" and "Felice A. Beato", it was long assumed that there was one photographer who somehow managed to photograph at the same time in places as distant as Egypt and Japan. But in 1983 it was shown by Chantal Edel[3] that "Felice Antonio Beato" represented two brothers, Felice Beato and Antonio Beato, who sometimes worked together, sharing a signature. The confusion arising from the signatures continues to cause problems in identifying which of the two photographers was the creator of a given image.

Mediterranean, the Crimea and India

Little is certain about Felice Beato's early development as a photographer, though it is said that he bought his first and only lens in Paris in 1851.[4] He probably met British photographer James Robertson in Malta in 1850 and accompanied him to Constantinople in 1851. Robertson had been an engraver at the Imperial Ottoman Mint since 1843 and had probably taken up photography in the 1840s.[5] In 1853 the two began photographing together and they formed a partnership called "Robertson & Beato" either in that year or in 1854 when Robertson opened a photographic studio in Pera, Constantinople. Robertson and Beato were joined by Beato's brother Antonio on photographic expeditions to Malta in 1854 or 1856 and to Greece and Jerusalem in 1857. A number of the firm's photographs produced in the 1850s are signed "Robertson, Beato and Co." and it is believed that the "and Co." refers to Antonio.[6]

In late 1854 or early 1855 James Robertson married the Beato brothers' sister, Leonilda Maria Matilda Beato. They had three daughters, Catherine Grace (b. 1856), Edith Marcon Vergence (b. 1859) and Helen Beatruc (b. 1861).[4]

In 1855 Felice Beato and Robertson travelled to Balaklava, Crimea where they took over reportage of the Crimean War following Roger Fenton's departure. They photographed the fall of Sebastopol in September 1855, producing about 60 images.[7]

In February 1858 Felice Beato arrived in Calcutta and began travelling throughout Northern India to document the aftermath of the Indian Rebellion of 1857.[8] During this time he produced possibly the first-ever photographic images of corpses.[9] It is believed that for at least one of his photographs taken at the palace of Secundra Bagh in Lucknow he had the skeletal remains of Indian rebels disinterred or rearranged to heighten the photograph's dramatic impact (see events at Taku Forts). He was also in the cities of Delhi, Cawnpore, Meerut, Benares, Amritsar, Agra, Simla and Lahore.[10] Beato was joined in July 1858 by his brother Antonio, who later left India, probably for health reasons, in December 1859. Antonio ended up in Egypt in 1860, setting up a photographic studio in Thebes in 1862.[11]

China

In 1860 Felice Beato left the partnership of "Robertson & Beato", though Robertson retained use of the name until 1867. Beato was sent from India to photograph the Anglo-French military expedition to China in the Second Opium War. He arrived in Hong Kong in March and immediately began photographing the city and its surroundings as far as Canton. Beato's photographs are some of the earliest taken in China.

While in Hong Kong, Beato met Charles Wirgman, an artist and correspondent for the Illustrated London News. The two accompanied the Anglo-French forces travelling north to Talien Bay, then to Pehtang and the Taku Forts at the mouth of the Peiho, and on to Peking and the suburban Summer Palace, Qingyi Yuan. Wirgman's (and others') illustrations for the Illustrated London News are often derived from Beato's photographs of the places on this route.

Taku Forts

Beato's photographs of the Second Opium War are the first to document a military campaign as it unfolded, doing so through a sequence of dated and related images. His photographs of the Taku Forts represent this approach on a reduced scale, forming a narrative recreation of a battle. The sequence of images shows the approach to the forts, the effects of bombardments on the exterior walls and fortifications and finally the devastation within the forts, including the bodies of dead Chinese soldiers. Interestingly, the photographs were not taken in this order, as the photographs of dead Chinese had to be taken first before the bodies were removed; only then was Beato free to take the other views of the exterior and interior of the forts. In albums of the time these photographs are placed in such a way as to recreate the sequence of the battle.[12]

Beato's images of the Chinese dead — he never photographed British or French dead — and his manner of producing them particularly reveal the ideological aspects of his photojournalism. Dr. David F. Rennie, a member of the expedition, noted in his campaign memoir, “I walked round the ramparts on the West side. They were thickly strewn with dead — in the North-West angle thirteen were lying in one group around a gun. Signor Beato was there in great excitement, characterising the group as ‘beautiful’ and begging that it might not be interfered with until perpetuated by his photographic apparatus, which was done a few minutes afterwards…”.[13] The resultant photographs are a powerful representation of military triumph and British imperialist power, not least for the purchasers of his images: British soldiers, colonial administrators, merchants and tourists. Back in Britain Beato's images were used to justify the Opium (and other colonial) Wars and they shaped public awareness of the cultures that existed in the East.

Summer Palace

Just outside Peking, Beato took photographs at the Summer Palace, Qingyi Yuan (Garden of Clear Ripples), a private estate of the Chinese emperor comprising palace pavilions, temples, a large artificial lake and gardens. Some of these photographs, taken between 6 and 18 October 1860, are haunting, unique images of buildings that were plundered and looted by the Anglo-French forces beginning on the 6 October, and then, on the 18 and 19 October, set to the torch by the British First Division on the orders of Lord Elgin as a reprisal against the emperor for the torture and deaths of twenty members of an Allied diplomatic party. Among the last photographs that Beato took in China at this time were portraits of Lord Elgin, arrived in Peking to sign the Convention of Peking, and Prince Kung, who signed on behalf of the Xianfeng Emperor.

Beato had returned to England by November 1861, and during that winter he sold four hundred of his photographs of India and China to Henry Hering, a London commercial portrait photographer. Hering had them duplicated and then resold them. When they first went on sale single views were offered at 7 shillings, while the complete India series was priced at £54 8s and the complete China series at £37 8s. Knowing that by 1867 the average per capita income in England and Wales had climbed to £32 per year puts the price of Beato's photographs into perspective.

Japan

By 1863 Beato had moved to Yokohama, Japan, joining Charles Wirgman who had been there since 1861. The two formed and maintained a partnership called “Beato & Wirgman, Artists and Photographers” during the years 1864–1867. Wirgman again produced illustrations derived from Beato's photographs while Beato photographed some of Wirgman's sketches and other works. Beato's Japanese photographs include portraits, genre works, landscapes, cityscapes and a series of photographs documenting the scenery and sites along the Tōkaidō, the latter series recalling the ukiyo-e of Hiroshige and Hokusai. This was a significant time to be photographing in Japan since foreign access to (and within) the country was greatly restricted by the Shogunate. Beato's images are remarkable not only for their quality, but for their rarity as photographic views of Edo period Japan.

Beato was very active while in Japan. In September 1864 he was an official photographer on the military expedition to Shimonoseki. The following year he produced a number of dated views of Nagasaki and its surroundings. From 1866 he was often (gently) caricatured in Japan Punch, which was founded and edited by Wirgman. In an October 1866 fire that destroyed much of Yokohama, Beato lost his studio and negatives, and he spent the next two years working vigorously to produce replacement material. The result was two volumes of photographs, ‘Native Types’, containing 100 portraits and genre works, and ‘Views of Japan’, containing 98 landscapes and cityscapes. Many of the photographs were hand-coloured, a technique that in Beato's studio successfully applied the refined skills of Japanese watercolourists and woodblock printmakers to European photography. From 1869 to 1877 Beato, no longer partnered with Wirgman, ran his own studio in Yokohama called “F. Beato & Co., Photographers” with an assistant named H. Woolett and four Japanese photographers and four Japanese artists. Kusakabe Kimbei was probably one of Beato's artist-assistants before becoming a photographer in his own right. Beato photographed with Ueno Hikoma and others, and possibly taught photography to Raimund von Stillfried.

In 1871 Beato served as official photographer with the United States naval expedition of Admiral Rodgers to Korea. The views Beato took on this expedition are the earliest confirmed photographs of the country and its inhabitants.

While in Japan, Beato did not confine his activities to photography, but also engaged in a number of business ventures. He owned land and several studios, was a property consultant, had a financial interest in the Grand Hotel of Yokohama and was a dealer in imported carpets and women's bags, among other things. He also appeared in court on several occasions, variously as plaintiff, defendant and witness. On 6 August 1873 Beato was appointed Consul General for Greece in Japan, a fact that possibly supports the case for his origins being in Corfu.

In 1877, Beato sold most of his stock to the firm, Stillfried & Andersen, who then moved into his studio. In turn, Stillfried & Andersen sold the stock to Adolfo Farsari in 1885. Following the sale to Stillfried & Andersen, Beato apparently retired for some years from photography, concentrating on his parallel career as a financial speculator and trader. On 29 November 1884 Beato left Japan, ultimately landing in Port Said, Egypt. It was reported in a Japanese newspaper that he had lost all his money on the Yokohama silver exchange.

Later years

From 1884 to 1885 Beato was the official photographer of the expeditionary forces led by Baron (later Viscount) G.J. Wolseley to Khartoum, Sudan in relief of General Charles Gordon. None of the photographs Beato took in Sudan are known to have survived.

Briefly back in England, in 1886 Beato lectured the London and Provincial Photographic Society on photographic techniques. But by 1888 he was photographing in Asia again, this time in Burma, where from 1896 he operated a photographic studio (called ‘The Photographic Studio’) as well as a furniture and curio business in Mandalay, with a branch office in Rangoon. Examples of his mail order catalogue — affixed with Beato's own photographs of the merchandise on offer — are in the possession of at least two photographic collections. Knowledge of his last years is as sketchy as that of his early years; Beato may or may not have been working after 1899, but in January 1907 his company, F. Beato Ltd., went into liquidation. The discovery in 2009 of Beato's death certificate indicates that he died on 29 January 1909 in Florence, Italy. The death certificate also notes that he was born in Venice in 1832.

Photography

Photographs of the 19th century often now show the limitations of the technology used, yet Felice Beato managed to successfully work within and even transcend those limitations. He predominantly produced albumen silver prints from wet collodion glass-plate negatives. Beyond aesthetic considerations, the long exposure times needed by this process must have been a further stimulus to Beato to frame and position the subjects of his photographs carefully. Apart from his portrait-making, he often posed local people in such a way as to set off the architectural or topographical subjects of his images, but otherwise people (and other moving objects) are sometimes rendered a blur or disappear altogether during the long exposures. Such blurs are a common feature of 19th century photographs.

Like other 19th century commercial photographers, Beato often made copy prints of his original photographs. The original would have been pinned to a stationary surface and then photographed, producing a second negative from which to make more prints. The pins used to hold the original in place are sometimes visible in copy prints. In spite of the limitations of this method, including the loss of detail and degradation of other picture elements, it was an effective and economical way to duplicate images.

Beato pioneered and refined the techniques of hand-colouring photographs and making panoramas. He may have started hand-colouring photographs at the suggestion of Wirgman or he may have seen the hand-coloured photographs made by partners Charles Parker and William Parke Andrew.[14] Whatever the inspiration, Beato's coloured landscapes are delicate and naturalistic and his coloured portraits, though more strongly coloured than the landscapes, are also excellent.[15] As well as providing views in colour, Beato worked to represent very large subjects in a way that gave a sense of their vastness. Throughout his career, Beato's work is marked by spectacular panoramas, which he produced by carefully making several contiguous exposures of a scene and then joining the resulting prints together, thereby re-creating the expansive view. The complete version of his panorama of Pehtang comprises nine photographs joined together almost seamlessly for a total length of more than 2.5 metres (8 ft).

While the signatures he shared with his brother are one source of confusion in attributing images to Felice Beato, there are additional difficulties in this task. When Stillfried & Andersen bought up Beato's stock they subsequently followed the common practice of 19th century commercial photographers of reselling the photographs under their own name. They (and others) also altered Beato's images by adding numbers, names and other inscriptions associated with their firm in the negative, on the print or on the mount. For many of Beato's images that were not hand-coloured, Stillfried & Andersen produced hand-coloured versions. All of these factors have caused Beato's photographs to be frequently misattributed to Stillfried & Andersen. Fortunately, Beato captioned many of his photographs by writing in graphite or ink on the back of the print. When such photographs are mounted, the captions can still often be seen through the front of the image and read with the use of a mirror. Besides helping in the identification of the subject of the image and sometimes in supplying a date for the exposure, these captions provide one method of identifying Felice Beato as the creator of many images.

Selected photographs

Photographs are indicated with Beato's own titles or titles from his era, followed by a descriptive title and the date of exposure.

-

- Balaklava Harbour, Crimea

- View of Balaklava Harbour, Crimea (with, or as an assistant to, James Robertson), 1855

-

- Interior of the Secundra Bagh after the slaughter of 2,000 rebels by the 93rd Highlanders and 4th Punjab Regt.

- View of the ruins of Sikandarbagh Palace showing the skeletal remains of rebels in the foreground, Lucknow, India, 1858

-

- Chutter Manzil Palace, with the King's Boat in the Shape of a Fish

- View of one of the Chattar Manzil [Umbrella Palaces] showing the King's boat called The Royal Boat of Oude on the Gomti River. Lucknow, India, 1858–1860

-

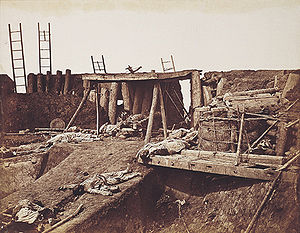

- Interior of Angle of North Fort Immediately after Its Capture, 21st August, 1860

- Partial view of the ruins of the Upper North Taku Fort, showing dead soldiers, Taku (now Dagu), near Tientsin (now Tianjin), China, 1860

-

- North and East Corner of the Wall of Pekin

- Panorama of the northeast corner watchtower, walls, and Dongzhi Gate of the Inner City, Peking (now Beijing), China, 1860

-

- Imperial Summer Palace before the Burning, Yuen-Ming-Yuen (sic), Pekin, October 18th, 1860

- View of the Belvedere of the God of Literature [Wen Chang Di Jun Ge] (now known as the Studio of Literary Prosperity or Wen Chang Ge), Garden of the Clear Ripples [Qing Yi Yuan] (now known as the Summer Palace or Yihe Yuan), Peking (now Beijing), China, 1860

-

- Portrait of Prince Kung, Brother of the Emperor of China; who Signed the Treaty, 1860

- Portrait of Prince Yixin (also known as Prince Gong), son of Daoguang, Emperor of China, seated in an armchair, Peking (now Beijing), China, 1860

-

- Panorama of Yedo (sic) from Atagoyama

- Panorama of Edo (now Tokyo) showing daimyo residences, Japan, 1865 or 1866

-

- Dai Bouts at Kamakura

- View of the Daibutsu [Great Buddha], Kotokuin Temple, Kamakura, Japan, 1860s

-

- Scene Along the Tokaido

- View of houses and people on the Tōkaidō, Japan, 1867–1868

-

- The Ford at Sakawa-Nagawa

- View of porters at a ford on a river, Japan, 1863–1885

-

- The Shimabara-han Fief Second Residence

- Partial view of the Shimazu (also known as Satsuma) clan's Takanawa daimyo residence on the Tōkaidō, Edo (now Tokyo), Japan, 1863[16]

-

- Woman Using Cosmetic

- Vignette of a woman using cosmetics, Japan, 1863–1885

Notes

- ↑ Bennett 2009, 241. Recent scholarship had uncovered an application by Beato for a travel permit in 1858 that included information suggesting he was born in 1833 or 1834 on the island of Corfu. Dobson, "'I been to keep up my position'", 31. Earlier sources had given his birth date as 1825 or ca. 1825, but these dates may have been confused references to the possible birth date of his brother, Antonio. However, the death certificate discovered in 2009 provides the first definitive evidence of Beato's dates and places of birth and death.

- ↑ Bennett 2009, 241; Dobson, "'I been to keep up my position'", 31. Beato has long been described as British, Italian, Corfiot Italian, and/or Greek. The peculiarities of the movements of his family and of early nineteenth century history in the Adriatic mean that Felice Beato can justifiably be described by all these terms. Corfu was on and off part of Venetian territory from 1386 until 1815, when the Treaty of Paris placed it and the other Ionian Islands under British "protection". Corfu was finally ceded to Greece in 1864. A line of the Beato family is recorded as having moved to Corfu in the 17th century and was one of the noble Venetian families that ruled the island during the Republic of Venice. Gray, 68.

- ↑ Zannier 1983, n.p.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Clark, Fraser, and Osman, 90.

- ↑ Broecker, 58; Clark, Fraser, and Osman, 89, 90.

- ↑ Oztuncay, 24; Clark, Fraser, and Osman, 90–91.

- ↑ Auer and Auer; Broecker, 58.

- ↑ Harris, 23; Dehejia, 121; Auer and Auer; Masselos 2000, 1. Gernsheim states that Beato and Robertson both travelled to India in 1857, but it is now generally accepted that Beato travelled there alone. Gernsheim, 96.

- ↑ Turner, 447.

- ↑ Harris, 23; Clark, Fraser, and Osman, 91–92.

- ↑ Clark, Fraser, and Osman, 90, 91.

- ↑ Harris 1999.

- ↑ Quoted in Griffiths.

- ↑ Bennett 1996, 39.

- ↑ Bennett quotes and summarises collector Henry Rosin's appraisal of Beato's hand-coloured photographs. Bennett 1996, 43; Robinson, 48.

- ↑ Recent research strongly suggests that this image may in fact show the daimyo residence of Shimazu Awajinokami of the Satohara clan, and that of the Matsudaira family of the Shimabara clan. Nagasaki University Library.

References

- Auer, Michèle, and Michel Auer. Encyclopédie internationale des photographes de 1839 à nos jours/Photographers Encyclopaedia International 1839 to the Present (Hermance: Editions Camera Obscura, 1985).

- Bachmann Eckenstein Art & Antiques. Accessed 3 April 2006.

- Banta, Melissa, and Susan Taylor, eds. A Timely Encounter: Nineteenth-Century Photographs of Japan (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Peabody Museum Press, 1988).

- Bennett, Terry. 'Early Japanese Images' (Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1996).

- Bennett, Terry. Felice Beato and the United States Expedition to Korea of 1871, Old Japan. Accessed 3 April 2006.

- Bennett, Terry. History of Photography in China, 1842-1860 (London: Bernard Quaritch Ltd., 2009).

- Bennett, Terry. Korea: Caught in time (Reading, UK: Garnet Publishing Limited, 1997).

- Bernard J Shapero Rare Books London, at Ideageneration.co.uk, Photo-London. Accessed 3 April 2006.

- Best, Geoffrey. Mid-Victorian Britain, 1851–75 (London: Fontana Press, 1971).

- Blau, Eve, and Edward Kaufman, eds. Architecture and Its Image: Four Centuries of Architectural Representation, Works from the Collection of the Canadian Centre for Architecture (Montréal: Centre Canadien d'Architecture/Canadian Centre for Architecture, 1989).

- Boston University Art Gallery. Of Battle and Beauty: Felice Beato's Photographs of China. Accessed 3 April 2006.

- Broecker, William L., ed. International Center of Photography Encyclopedia of Photography (New York: Pound Press, Crown Publishers, 1984).

- Brown University Library; Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection: Photographic views of Lucknow taken after the Indian Mutiny. Accessed 3 April 2006.

- Canadian Centre for Architecture; Collections Online, s.v. "Beato, Felice". Accessed 29 September 2005.

- Canadian Centre for Architecture; Collections Online, "Panorama of Edo (now Tokyo)", PH1981:0809:001-005. Accessed 10 March 2006.

- Clark, John. Japanese Exchanges in Art, 1850s to 1930s with Britain, continental Europe, and the USA: Papers and Research Materials (Sydney: Power Publications, 2001).

- Clark, John, John Fraser, and Colin Osman. "A revised chronology of Felice (Felix) Beato (1825/34?–1908?)". In Japanese Exchanges in Art, 1850s to 1930s with Britain, Continental Europe, and the USA: Papers and Research Materials. (Sydney: Power Publications, 2001).

- Dehejia, Vidya, et al. India through the Lens: Photography 1840–1911 (Washington, D.C.: Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery; Ahmedabad: Mapin Publishing; Munich, Prestel, 2000).

- Dobson, Sebastian. "'I been to keep up my position': Felice Beato in Japan, 1863–1877", in Reflecting Truth: Japanese Photography in the Nineteenth Century, ed. Nicole Coolidge Rousmaniere, Mikiko Hirayama (Amsterdam: Hotei Publishing, 2004)

- Dobson, Sebastian. "Yokohama Shashin". In Art & Artifice: Japanese Photographs of the Meiji Era — Selections from the Jean S. and Frederic A. Sharf Collection at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (Boston: MFA Publications, 2004), 16, 38.

- George Eastman House: "India"; "Technology and War". Accessed 3 April 2006.

- Gernsheim, Helmut. The Rise of Photography: 1850–1880: The Age of Collodion (London: Thames and Hudson Ltd., 1988).

- Gray, Ezio. Le terre nostre ritornano... Malta, Corsica, Nizza. De Agostini Editoriale. Novara, 1943

- Griffiths, Alan. Second Chinese Opium War (1856–1860), Luminous-Lint. Accessed 3 April 2006.

- Harris, David. Of Battle and Beauty: Felice Beato's Photographs of China (Santa Barbara: Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 1999).

- Masselos, Jim and Narayani Gupta. Beato's Delhi 1857, 1997 (Delhi: Ravi Dayal, 2000).

- Masselos, Jim. The Photographer's Gaze: Seeing 19th Century India, VisAsia.

- Musée Nicéphore Niépce; Collection du musée Niépce. Thé/Laque/Photographie. Accessed 3 April 2006. (French)

- Nagasaki University Library; Japanese Old Photographs in Bakumatsu-Meiji Period, s.v. "F. Beato". Accessed 24 January 2007.

- The New York Public Library, s.v. "Beato, Felice". Accessed 3 April 2006.

- Osman, Colin. "Invenzione e verità sulla vita di Felice Beato". In 'Felice Beato: Viaggio in Giappone, 1863–1877', eds. Claudia Gabriele Philipp, et al. (Milan: Federico Motta, 1991), p. 17, fig. 14. (Italian)

- Oztuncay, Bahattin. James Robertson: Pioneer of Photography in the Ottoman Empire (Istanbul: Eren, 1992), 24–26.

- Pare, Richard. Photography and Architecture: 1839–1939 (Montréal: Centre Canadien d'Architecture/Canadian Centre for Architecture; New York: Callaways Editions, 1982).

- Peabody Essex Museum Collections; Photography. Accessed 3 April 2006.

- Perez, Nissan N. Focus East: Early Photography in the Near East, 1839–1885 (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. 1988).

- Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology. The World in a Frame: Photographs from the Great Age of Exploration, 1865–1915, s.v. "Felice Beato". Accessed 3 April 2006.

- Rahman, Ram. Camera Indica: Photography as history and memory in the 19th century, Frontline Volume 18, Issue 15, 21 July - 3 August 2001. Accessed 3 April 2006.

- Robinson, Bonnell D. "Transition and the Quest for Permanence: Photographer and Photographic Technology in Japan, 1854–1880s". In A Timely Encounter: Nineteenth-Century Photographs of Japan, ed. Melissa Banta, Susan Taylor (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Peabody Museum Press, 1988), 48.

- Rosenblum, Naomi. A World History of Photography (New York: Abbeville Press, 1984).

- Satow, Sir Ernest, A Diplomat in Japan (London: Seeley Service, 1921. Many reprints. Beato is mentioned at the beginning of Chapter X, Shimonoseki — Naval Operations)

- Turner, Jane, ed. The Dictionary of Art, vol. 3 (New York: Grove, 1996).

- Union List of Artists Names, s.v. "Beato, Felice". Accessed 3 April 2006.

- Vintage Works, Ltd., s.v. "Robertson, James". Accessed 3 April 2006.

- Vintage Works, Ltd., s.v. "Robertson, James and Beato, Felice". Accessed 3 April 2006.

- Zannier, Italo. Antonio e Felice Beato (Venice: Ikona Photo Gallery, 1983).

- Zannier, Italo. Verso oriente: Fotografie di Antonio e Felice Beato (Florence: Alinari, 1986).

External links

- A biography of the artist Felice Beato from the J. Paul Getty Museum

- New York Public Library Digital Gallery, Beato image of Shrine steps where Shogun Minamoto no Sanetomo was killed

- The Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives' gallery of Felice Beato photographs, 67 images including landscapes and portraits.